Object Oriented Programming Introduction

****IMPORTANT NOTE**** As is expanded upon below, this goes waaaay beyond what you will likely be able to fully understand at this point, but preliminary exposure to it will be helpful in the grand scheme of things.

Pedagogical Scope & Sequence Pre-amble

At this stage in your Java exposure, there are many things which could be introduced, but of the major concepts, no one thing can be thoroughly understood without completing coverage of other supporting material. So, for example, we could move into arrays, and arrays of objects, but full understanding of that will not be possible until you gain a better understanding of objects. Or we could move into objects, but be unable to use arrays in the instruction. For these kinds of reasons, that's why more than one "spiral" is needed for full understanding. And through multiple spirals, "exposure" adds to experience, and gradually all of the pieces are in place with which you can fully appreciate all of those pieces.

We will now we enter into your first exposure to, indeed your first spiral through, objects. And based on the above points, bear in mind that we don't have a lot now to "hang" this new knowledge on, and some of it will seem to be without obvious purpose. Never-the-less, much will have good purpose in and of itself. Furthermore, of all the fundamental concepts which we could enter into at this stage, there is no more fundamental fundamental than the object, when dealing with object oriented programming.

A Little History First

To understand the whys and wherefores of Object Oriented Programming (OOP), you need to place it within the historical context of programming development. Back in the mid to late '90s, when Java was being developed and coming to the fore, there were several movements in the programming world which were gaining attention. They included concepts such as "encapsulation", "polymorphism", and "inheritance". Encapsulation was the idea that the data of programs is most secure and reliable when protected from the affects of other programs. Polymorphism, as the name suggests, suggested that the particular methods and operators should be able to be used differently in different contexts. And inheritance was the idea to let new programs re-use stuff already designed, rather than re-inventing the wheel. Given that all of these ideas were actively being developed when Java was being developed, they were adopted by it, and other OOP programming languages. None of these concepts is necessarily bound to OOP, nor is OOP necessarily bound to them - with the possible exception of encapsulation.

A Little More History & The "Oriented" Part of Object Oriented Programming

By encapsulating all of the data and methods of a particular program, and sequestering them away from the troublesome influence and side effects of other programs, it necessitates a way of creating and managing an "instance" of that program, or put another way, creating and managing an "object" of that class. Before true encapsulation, it was possible to directly use data and methods of other programs, and as long as a program using another program did it wisely, no problems occurred. But if one program changed data of another program in a way that was not intended, then problems could - and very often did - occur. Better to have the methods of a particular program manipulate the data therein, in ways that it knows best. So with the development of specialized classes within a programming language such as Java, the orientation of the programmer becomes on the objects which he/she chooses to create in order to aid his/her own program. Hence "object oriented". So, if I want to, with Java, get input from the console: "what class shall I use? InputStreamReader, or BufferedReader, or some other existing class which specializes in getting input from the console?" This and other similar object oriented questions are what will drive my development, along with the development of my own classes.

Compare this to what came before, which was, well, simply not object oriented. Procedural programming is the best term to describe what went before OOP. Procedural programming was based on procedures (or methods) which would be called based on certain conditions. Java, and virtually all other programming languages also do this; it's just that what came before procedural programming did not, so back in its time, the "procedural' part of it was what was innovative. (Before procedural programming, were languages which used "goto" statements to manage the flow of control.) So anyway, moving forward, likely what follows OOP will also include most of what makes it useful, but there will be some other innovative feature which will take the lime-light.

What is an Object?

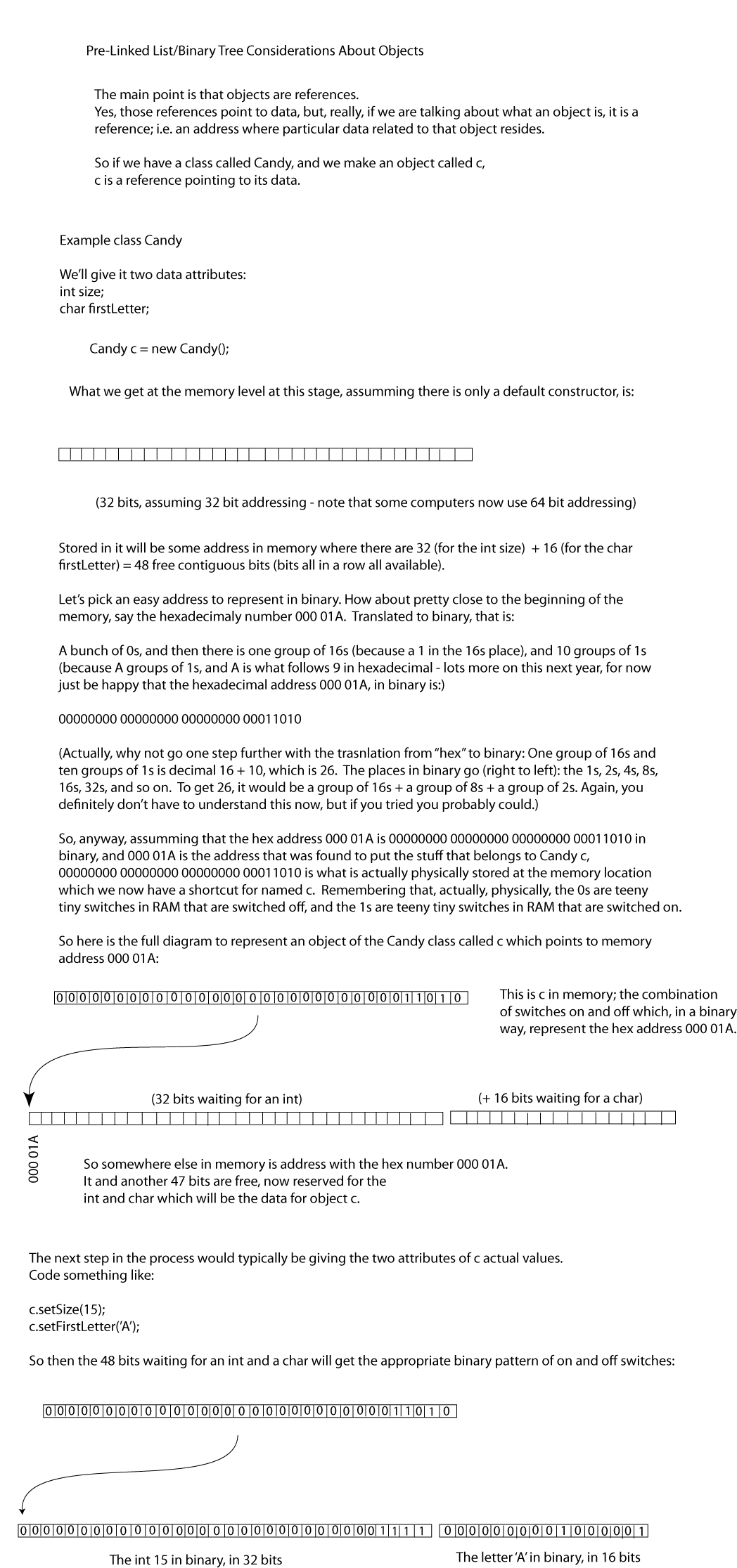

An object in Java is a reference to a place in memory which stores some specific data - anything from a simple boolean value to a large complex object. In a 32-bit system, an object is therefore 32 bits of computer memory, which stores a 32 bit address. In 32 bit computer "architecture", 2 ^ 32 , or around 4 billion bytes can be addressed, since there are around 4 billion combinations of on/off circuits that are possible between the binary memory address 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 and 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111. Rather than use binary for numbering memory addresses, or even decimal, it is more compact to reference memory addresses which have such a big a range of values with the hexadecimal numbering system. We thus, in a 32-bit system, will have address from 000 000 to FFF FFF (hexadecimal has the digits 0123456789ABCDEF). So a memory address might be @AAA237, for example (with the @ signifying that what follows is a memory address). So, really, that's what an object is, it's a series of on/off switches in memory, which we represent as the hexadecimal equivalent of the binary code of those on/offs, and which are the memory address of where the data associated with that address begins. (If you can get your head around that sophisticated, yet complete and correct definiton, kudos to you, but that's what an object really is. And if you can't - which is surely quite likely: an object is a reference to certain data.)

So much for keeping this a simple introduction.... But right from the start it is important to remember that the object itself is a 32 bit address of the data associated with it. Yes, we're more interested in working with the data than the address. But we need the address so that we can get to the data. And this leads to a major advantage of the "reference" nature of objects, which will be discussed next. And, by the way, that objects are references is not anything necessarily bound to OOP. It, along with concepts like polymorphism and inheritance are just great things that are "along for the ride" with the object oriented nature of OOP languages such as Java.

The Advantage of An Object Being a Reference

Since an object (itself) is a reference, when we assign a new object another object's value, we are simply copying (only) 32 bits of memory. Whereas if we were assigning the full data of one object to another object, we would be exactly doubling the amount of memory being taken up by that object. So let's say in another programming language (which does not have objects as references) there is an object which is some sort of multimedia, and takes up Megabytes of memory. By copying that object, we would be copying Megabytes of memory. Whereas in the "reference" system, we are only copying exactly 32 bits. You may be wondering why we would copy data in the first place, and the most important answer is that, in Java, whenever we move a piece of data to a method which will process it, we make a copy of it. So, if we were to sort a list of names, that list (or the reference to it)would need to be copied. It does not necessarily need to be so, but in keeping with the "encapsulation" mantra of protecting data from being incorrectly manipulated, even methods in Java can have their own data. So, when a piece of data is sent to a particular method, if that data is sent as an object, then a 32 bit reference, only, is sent and copied. But the data itself can still be worked on, since the method will have the address referencing it.

Primitives vs Objects (i.e. references)

Now is as good a time as any to get straight the difference between what we last looked at, and what we are now dealing with - primitives vs. objects. You can think of a Java type as being a kind of data which is defined both by its size (in terms of bits) and how it can be used (so is the data used for communicating text, or color, for example). So, a double is a 64 bit Java data type used for storing real number information. And a boolean is an 8 bit Java data type used for storing true/false values. Well, one Java type is a reference type; i.e. any object (or, anything made with the new operator - more on that shortly). A Java reference (i.e. Object) is a 32 bit type which is used for storing a memory address.

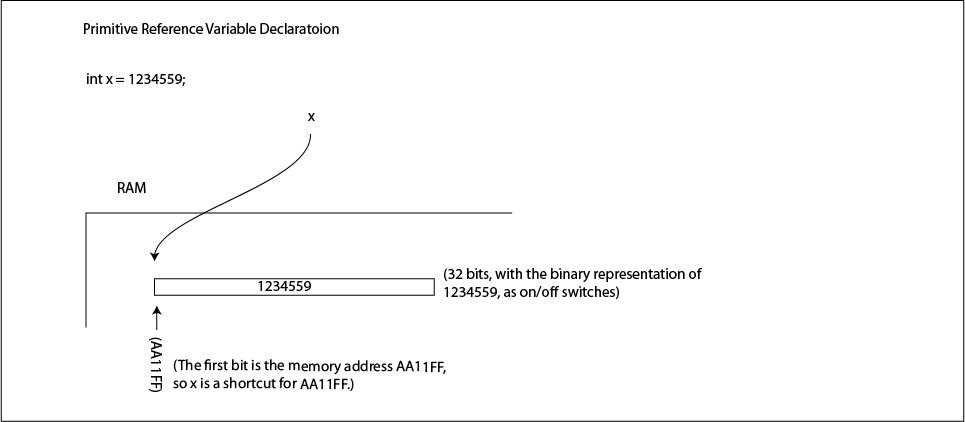

We call primitives "literals", because what is stored at the memory location which the variable identifier is a shortcut for, is literally a real number, or a character, etc. And "reference" objects are not literally the data they point to, rather they are the memory address where that data resides.

How Do We Make An Object?

The new operator is how we make a new object.

But first, consider how we make a new primitive. We simply write the type (int, char, double, etc.) and then we write the variable identifier, and then we use the assignment operator (=) to place the data there. "There" is a certain memory address, where, literally, that data will reside. And the variable identifier is just a shortcut for us to call it. (Consider a certain royal, officially called "His Honorable, Most High, Princely, Charles Alexander Mitchelle-Andrea Schmatz, King of Maroon III"; his friends would just call him "Chuck". In the same way, we don't call the real number held at @7A3 FF9, "7A3 FF9", rather we call it "x".) We thus say that a variable identifier is the name of a piece of data we are working with. Likewise we could say a variable itself is a named memory location.

Making a new primitive:

int x = 1234559;

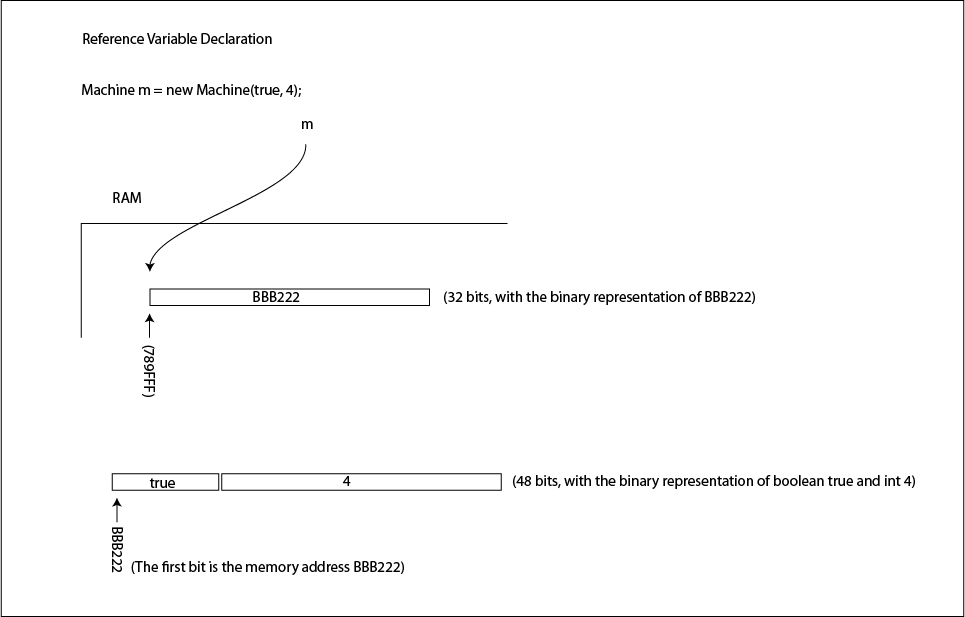

And so for making a new object, we do the same sort of thing, only we use the new operator. We need this extra bit of code in order to call the "constructor" of the new object, which will dictate how much memory needs to be reserved. With a primitive, we know; an int reserves 32 bits, a char reserves 16 bits, and so on. But the amount of memory needed for an object depends entirely on what makes up that object. Does the object have three ints, a boolean and four Strings, or does it have two booleans and a float? Whatever it has, the constructor will "know", and so the computer will find a place in memory (of contiguous bits - bits all in a row) which is free, and reserve that memory for the new object.

Making a new object:

Machine m = new Machine(true, 4);

So, in the above example, the new operator went looking for a place in memory where there was (16 + 32) 48 bits of contiguous memory, and it placed the boolean true and the int 4 there. Meantime, it took the address where the true value started to be written, and it wrote that address in the place in memory that will be called m from that point to when the m variable is no longer used. So let's say that this Machine object gets written starting at @BBB222, well BBB222 is what will be held by m (which, in turn is actually residing at another memory address, let's say @789FFF - m is a shortcut for memory address 789FFF.

****ANOTHER IMPORTANT NOTE**** The following diagram is for those who want to consolidate their understanding a bit more at this point.

It is actually from one of the most sophisticated pages of notes in the whole course, but it discusses exactly what is detailed above.